HISTORY OF THE TEA FACTORY

By Royston Ellis. May, 1996. The factory at the Hethersett tea plantation played an important part in the development of Sri Lanka’s tea industry, and in helping Pure Ceylon Tea to become renowned as the world’s favourite beverage. Tea from the Hethersett factory was the first to fetch the highest price in the world for silver tip tea from Ceylon. In 1891, Hethersett tea was auctioned in Mincing Lane, London for £1.10s.6d, over thirty times the then average price 1s0d for a pound of tea.

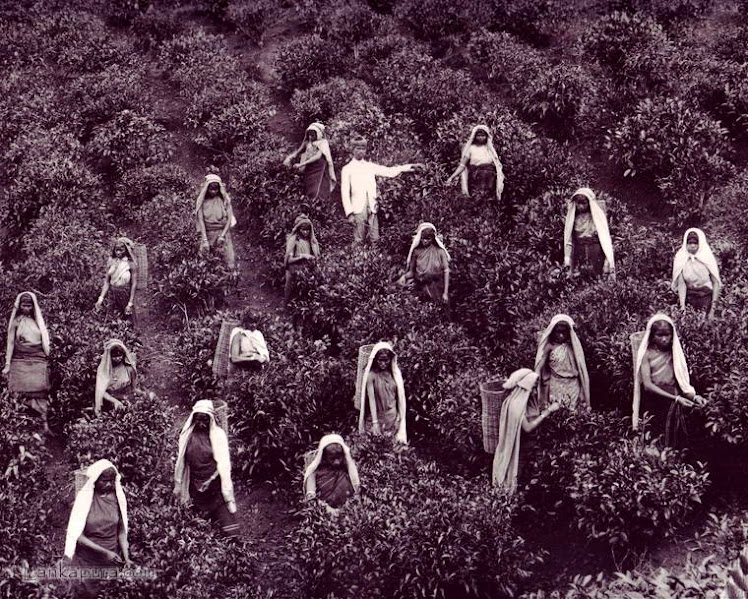

This was an exciting achievement for a new tea factory. Tea was first grown commercially in Ceylon (which became Sri Lanka in 1972) by a Scotsman, James Taylor, on a coffee estate named Loolecondera, near Kandy, in 1867. Taylor, with encouragement from Dr. Thwaites, the Director of The Royal Botanical Garden at Peradeniya, planted 20 acres of tea grown from seed imported from India. It was a wise move as, soon afterwards, a dreadful blight ravaged the coffee plantations on which Ceylon’s economy depended. Planters turned in desperation to tea and cinchona (for quinine) as alternative crops. Within a decade of Taylor’s planting there were 5000 acres of tea growing in the hills of Kandy and Nuwara Eliya. In response to requests to open up plantations, the government sold virgin crown land around Kandapola to pioneer planters in the 1870s. Among the bidders was Mr. W. Flowerdew. He was the first planter-proprietor, agent and resident manager of what became Hethersett Estate. This consisted of 250 acres of which he planted 150 with cinchona. Flowerdew was a pioneer. He camped in the wilderness he had bought, working alongside labourers hired in gangs from India. Before clearing and planting the land, he built himself a log cabin, using boards sawn from trees felled to open up the land. The roof was foliage used as thatch. It was a primitive and tough life. The name he chose for his plantation gave a clue about Flowerdew’s origins. He seems to have named it Hethersett after a village southwest of Norwich in England. Perhaps it was his home village since even today the distinctive name of Flowerdew is to be found in the Norwich area. The Tamil name for the plantation is Poopanie. Translated into English it means Flowers of Frost. It is picturesque way of describing the cold mist that occasionally descends on Hethersett, which is 6800 feet above sea level, although only six degrees from the Equator. Actually the plantation name, however apt, is a direct translation into Tamil from the English name of its original owner: Flowerdew. Flowerdew had a partner during his first year on the plantation, Jas. R. Jenkins, an experienced tea planter who advised him to grow tea as well as cinchona. History does not recall what happened to Flowerdew but by 1881 he seems to have sold the plantation. A temporary manager,[1] A.C.W. Clarke, was in charge and the estate was in the name of Jas. Whittall, with his own company, Whittall & Co., as agents. The agent’s role was vital in the early days of the tea industry. Usually an estate proprietor was an individual or company based in England who needed an agent in Colombo to provide support, and supplies, to the manager of the plantation. A broker handled the sale of the crop. Whittall & Co. remained as agents for a few years but ownership passed to Mr. J. MacAndrew. An experienced planter, K. MacAndrew, doubtless a relative, became the resident manager. In 1885, Hethersett consisted of 254 acres planted in tea and cinchona. Cinchona served as a cash crop while the MacAndrews were nurturing tea. K. MacAndrews was also the manager of the neighbouring estate, Denmark Hill. This was the beginning of a link that resulted in green leaf grown at Denmark Hill being processed into made tea at the Hethersett factory. The successful sale of the early shipments of Hethersett tea in London, and the record-breaking price selling price, in 1891, began the formidable reputation of the Hethersett mark, making it synonymous with Pure Ceylon Tea of quality. By 1897, Hethersett was swallowed up by the Nuwara Eliya Tea Estates Company Limited into a combined holding of 3000 acres. The Company, registered in London, had Leechman & Co., as agents in Colombo. It was an association with both companies which Hethersett that was to last 75, years until nationalisation. George Leechman founded his agency house in 1866. He was previously a partner with Wilson, Ritchie & Co. That company, was founded in 1830, eventually became part of Aitken Spence & Co., Ltd. the present managers of Hethersett. The tea factory that produced Hethersett’s silver tips (a hand-rolled, sun dried, whole leaf tea) and its Orange Pekoe, was located down hill from the present factory, where the village crèche now stands. It was a small wooden building that expanded under the direction of a dynamic young planter called John Mac Tier. Mac Tier arrived at Hethersett in 1900 when he was 27. There were 270 acres of tea then. He stayed for 25 years, dying suddenly in the old Hethersett factory when he was 52. There is a memorial plaque in the Holy Trinity Church, in Nuwara Eliya, “in affectionate memory”. During Mac Tier’s tenure, the owning company happily reported dividends of between 9% and 12% every year. Tea from the factory began its journey to market in tea chests carried by bullock carts down the rough tracks to the Railway station at Kandapola. The narrow gauge railway line was opened in 1903 (it closed in the 1940s) from Ragalla via Kandapola to Nuwara Eliya and Nanu Oya. At Nanu Oya the tea chests were transferred to the main, broad gauge line, and sent for delivery to the Colombo godowns. After auction, the tea chests went by steam ship to England or Australia. The journey by train from Nuwara Eliya to Kandapola took one hour as the toylike engine puffed and weaved through the hills. Its maximum speed was six miles per hour. Cyril Travers Nettleton, an unofficial police magistrate, was the planter at Hethersett for a couple of years after Mac Tier. He too, rests at Holy trinity Church, having been in charge of the Concordia Group, which includes Hethersett, when he died in 1944. He was succeeded at Hethersett, by A.J. Waterfall. During Waterfall’s time the original wooden factory in the village was burnt down. The head of a hill was scalped to create a plateau for the new factory which is the hotel of today. When it was built in the mid-1930s, it was regarded as a remarkable work of engineering. There was no water or stem to power it, or mains electricity, only the ingenious use of an oil fired engine with fly-wheels and pulleys to operate the large fans for withering the tea, and also the rollers and sifters. The factory produced top quality orthodox tea, both whole and broken leaf, for export. Tea grown on the neighbouring Denmark Hill estate was shuttled down to the factory in sacks along a wire stretched across the valley separating the two estates. The planters in charge of Hethersett during the 1940s to 1960s were personable, capable men from Britain. Gordon Windus, manager for most of the 1940s, was a member of the prestigious Hill Club in Nuwara Eliya. In May 1934 he wrote testily in the visitor’s book there, “I should like to suggest that peas from the garden instead of tinned peas are served.” Windus is remembered by the Hethersett villagers for the agricultural projects he started. These included a piggery in the village and a vegetable farm in the jungle at Kuruwatta. Planter John Bousfield used to surprise the labourers by working in the fields with them, pruning the tea bushes himself. It is said that the bushes he pruned yielded the most tea. Another British planter, J. M. E. Waring, who took over Hethersett in the late 1950s, and eventually, as group manager, supervised the closing down of the factory. He owned a horse which he used when inspecting the fields. He also raced this animal with a jockey, at the Nuwara Eliya race meets. In 1968, the Hethersett factory had passed its heyday. Its machinery was regarded as old fashioned and uneconomical. It was the time of cost cutting and so the factory was closed. The Hethersett green leaf was sent to other factories in the Concordia group for manufacture. For three years the factory was used as a warehouse for refuse tea, which is the fibrous reject after the manufacturing process. A few people were employed to sift the fibre and extract any remaining tea for local consumption. The residue was sold as fertiliser.

|